Personalizing portfolios at scale

with Direct Indexing

Direct indexing has existed for many years and is another way to invest in a collection of stocks. It is an investment process that registered-investment advisors and professional-wealth managers use to design portfolios for their clients based on their knowledge of their clients’ particular circumstances.

In a heavily regulated environment, wealth managers using direct indexing are registered professionals who are experienced in managing client portfolios, and they often leverage the services of an asset manager for further assistance.

While index-tracking ETFs and mutual funds provide indirect exposure to some or all of the constituents listed in an underlying index, wealth managers design an index that will help them to create a customized portfolio when using a direct-indexing approach.

The manager will invest for their client in a subset of the constituents of an index that the manager selects, designs, and advises the client that best meets their particular needs. This is referred to as a “client-designed index” or “CDI”.

In addition, the manager may achieve greater tax-efficiency for their client by employing tax-optimization algorithms in managing their client’s portfolio.

ESG Portfolio construction: Managers may seek a balance between taxes and tracking error

*See part 2 for ESG case study example

A wealth manager creates a CDI based on an underlying equity index with their requested modifications to reflect their clients’ preferences. However, CDI deviation relative to the underlying equity index is inevitable. Managers may create tracking error relative to the CDI by optimizing the portfolio to reduce or defer taxes. While there is a risk from such deviations, some investors have been willing to accept this risk in order to express their personal preferences.

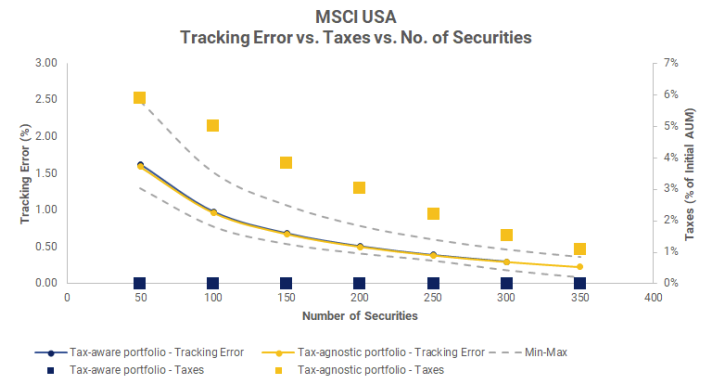

We examined the financial impact of tax optimization relative to the performance that would have been achieved if the manager invested in the underlying equity index. For the purposes of our analysis, we built multiple hypothetical, tax-aware portfolios that could be created by an investment advisor for her client (shown in Exhibit 1), to analyze if the number of securities in a portfolio could have influenced the balance between taxes and tracking error. While our portfolios varied in the number of positions, they all had the primary goal of reducing short-term taxes to zero and minimizing tracking error between the client’s portfolio and the underlying MSCI USA Index.

For reference, we also built hypothetical, tax-agnostic portfolios that aimed to minimize tracking error to the MSCI USA Index without tax considerations or turnover management.2

Each portfolio was held for three years, with the first portfolio starting in January 2001 and the last beginning in January 2019. Thus, our analysis covers the period starting in January 2001, and ending in December 2021.

We started each portfolio from cash and used historical prices for each rebalance, so realized and unrealized gains reflect what an investor could have achieved at the time. We used cash to simplify our analysis and avoid the additional complications associated with investors transitioning from tax-inefficient vehicles, which is outside the scope of this initial research.

In general, tracking error declined with a higher number of securities in the portfolio but at a progressively lower rate. This implies that the starting index could have been reasonably tracked by a subset of securities, and that increasing the number of securities beyond that number would have achieved only a marginal reduction in tracking error. The beta for all portfolios ranged between 0.99 and 1.01 and factor exposures were very similar to the underlying index. Taxes were accumulated over the life of the strategy and expressed as a percentage of the initial investment amount.

Interestingly, the tax-aware portfolio produced about the same level of tracking error as the tax-agnostic one, implying that using tax-aware optimization could have reduced or deferred taxes without incurring any meaningful increase in tracking error. As part of our exploratory analysis, we extended the strategies for a hypothetical 100-stock portfolio to five-, seven- and 10-year holding periods, finding that a longer holding period only increased tracking error relative to the tax-agnostic portfolio by 20 bps on average in the final year of the 10-year strategies.

For the remainder of this paper, we focus on three-year strategies rebalanced quarterly, which used historical market movements to drive rebalancing decisions.

Exhibit 1: Impact of portfolio size on tracking error and taxes

Wealth managers who look to tax-optimization algorithms to potentially defer taxes while tracking the underlying indexes efficiently, may want to consider the number of securities in a given portfolio in light of an investor’s risk tolerance. We found that an investor with a risk tolerance of approximately 1% tracking error who followed a three-year strategy between 2001 and 2020, targeting 100 stocks from the MSCI USA Index within a tax-optimized framework, would have saved about 5% of their initial investment on average by reducing the taxes they incurred during each portfolio rebalance.

1 We note that the MSCI USA Index and MSCI’s other indexes are not investment advice, but rather consist of mathematical calculations performed according to a transparent, rules-based methodology that measure the performance of an investment opportunity set such as a country, region, sector, factor (e.g., momentum), style or other investment category (e.g., ESG). MSCI has no assets under management, provides no investment advice or recommendations of any sort, gives no personalized advice (CDI licensees request their own specifications), does not promote any index-linked financial products or manner of investment, and provides disclaimers clearly stating this and requires its licensees to provide these disclaimers.

2 We used MSCI’s Open Optimizer to construct portfolios with constraints and MSCI’s Barra® US Total Equity Market Model for Long-term Investors (USSLOW) as the underlying risk model.

3 Higher portfolio turnover may not always imply higher taxes. The amount of taxes generated can be influenced by market cycles, time-series and cross-sectional volatility, among other things.

4 Tax-aware portfolios may not always result in zero taxes. Taxes paid at portfolio liquidation can significantly vary depending on the investor’s tax situation and tax-management capabilities and are not included in the analysis. Note that period-ending liquidation can trigger potentially significant tax consequences.

Explore more on Direct Indexing from MSCI

‘What is Direct Indexing’ Infographic

MSCI EAFE Expanded ADR Index

More from MSCI

Matching Portfolios and Clients’ Expected Returns, with Factors

Wealth managers face the challenge of matching clients’ objectives with an ever-growing set of investment products. Standard practice is to build strategic asset-allocation models based on broad capital-market assumptions. But we present a new approach.

ESG and Climate Adviser Guide

The ESG and Climate Guide for Financial Advisers by MSCI ESG Research explains key sustainable investing concepts from the difference between ESG and impact investing to how to use reporting to learn about your client’s unique values.

.

40% Women on Boards — the New Frontier

The number of women on boards continues to rise. While a 30% board gender diversity target has long been the magic number, the continued evolution of boards, both by choice and by regulation, means 40% women on boards is becoming the new frontier.